The Chinese-speaking world, including China itself but also large Asian and worldwide diaspora, are in the midst of celebrating the Lunar New Year. While many people are aware of the festivities, mostly from the red-and-gold decorations that pop up in shop windows, few know what they are all about.

In fact, the Lunar New Year, also known as Chinese New Year or Spring Festival, is a perfect metaphor for intercultural curiosity, stereotypes, and, ultimately, opportunities to understand each other better. Despite its origins, today it is a worldwide celebration, thanks to over sixty million ethnic Chinese people around the globe. Yet, most people who witness it outside of China compare Lunar New Year iconography to their home traditions, often with somewhat misleading results.

Cultural misinterpretation can have far-reaching consequences in a world where China plays a central role in politics, business, and daily life — look around yourself, and you will surely spot things made there. For specific business-related examples, you might want to watch my recent video on the way Western brands advertise for Chinese New Year. But right now, I would like to hit a lighter chord and illustrate the cultural nuances of Lunar New Year with the most striking feature of the festivities: the animals in its traditional calendar.

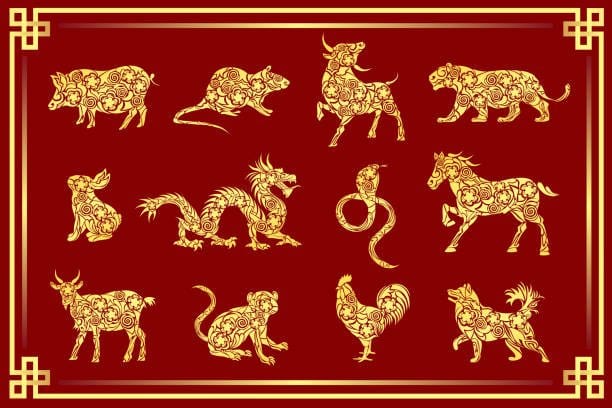

China’s zodiac features twelve animals that take annual turns according to a sequence that children learn to recite at school. The upcoming animal sign is common knowledge to all with an interest in Asian traditions, but the subtle significance of each one often gets lost in translation. Before we get to the Dragon Year we inaugurate in 2024, one with a special stance among all other creatures, let’s take recent years as examples.

Take the tiger, for instance, the zodiac sign two years back, most recently inaugurated in 2022. In the Western mind, the tiger is a fierce and fearsome creature, symbolizing the untamed forces of nature. Tigers in the Asian traditions, though powerful, are calm and wise, bearing the Chinese character of “king” (王) on their forehead. In that respect, they resemble the lion in Western traditions: recall how many European nations feature lions in their flags or coats-of-arms, but practically none with tigers. In addition to the apparent courage, Lunar New Year Tigers also stand for generosity and protection.

We are currently closing the Year of the Rabbit, a creature that often inspires cultural confusion. In ancient traditions, rabbits were messengers between the physical and the spiritual realms in both East and West. For instance, observers in both Europe and Asia imagined a rabbit on the Moon for some reason. However, the only festive rabbit we know in the West today is the Easter Bunny, admired mainly for its cuteness. Recent associations include cartoon rabbits like Bugs Bunny and Roger Rabbit, which pop up in special editions of Western brands in Asia. That gives little justice to the traditional Lunar New Year’s Rabbit, which stands for grace, elegance, and patience.

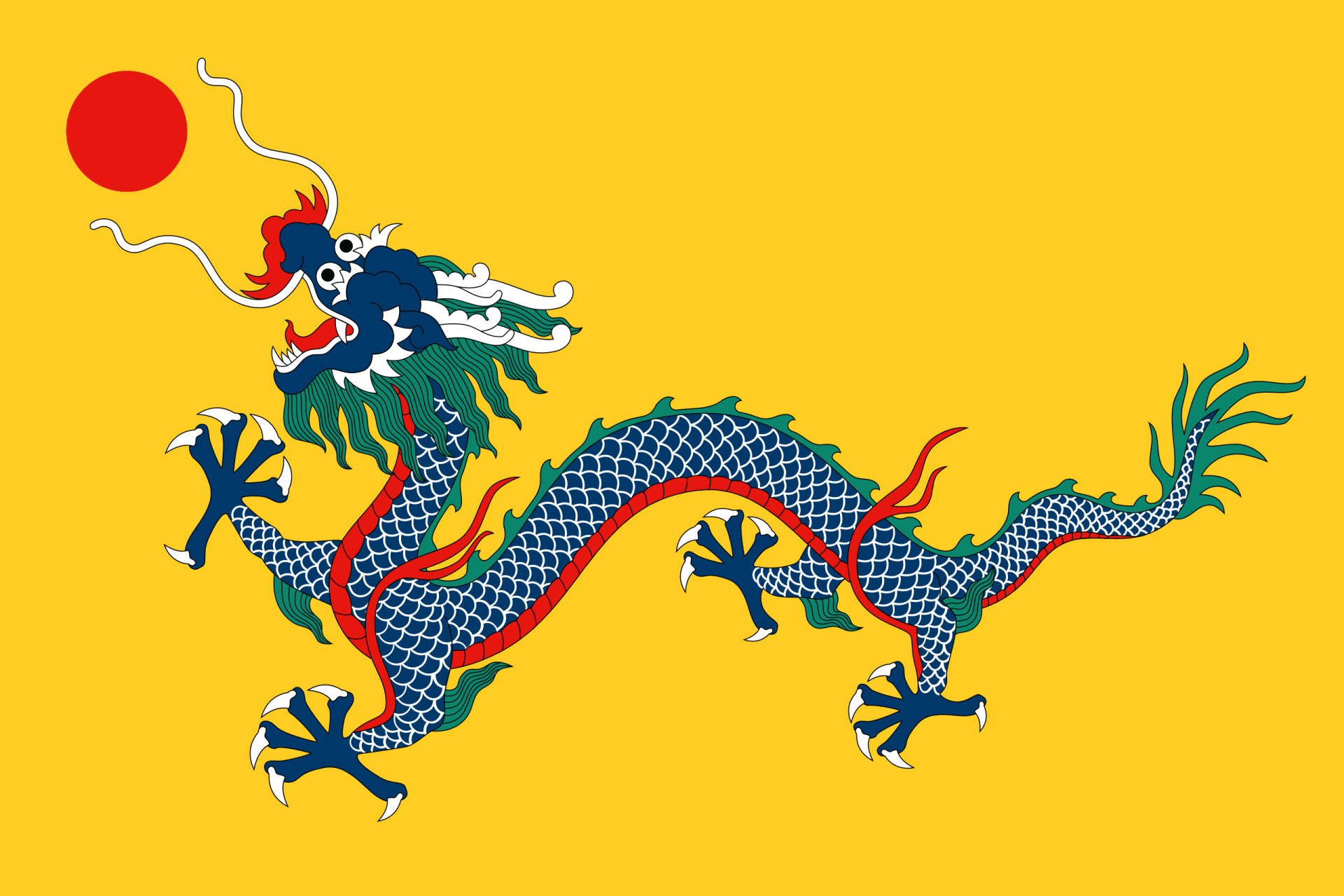

That brings us to the upcoming Year of the Dragon, a creature with a special place in the zodiac. For one, Dragon is the only mythical animal in the calendar. For another, it is not any of the dragons that spring to mind in Judeo-Christian traditions—the ones that Saint George slays in paintings and sculptures, often with multiple heads. On the contrary, this Dragon stands for wisdom, tradition, and the benevolent forces of nature with which people should seek harmony. It is also the nation’s protector: China’s imperial flag was a dragon reaching for the sun. The impressive 3D laser and drone dragons that glide overhead this year’s celebrations never scare merrymakers: they bring the promise of much-needed calm, safety and harmony.

And that is precisely what we at SIETAR Europa wish for all of our members and readers.

Happy Dragon Year!

Author: Gabor Holch

Image Sources: Wikipedia; Shutterstock.